45 The end of the long road

Published in the Forverts on February 20th, 1947

In Satz’s role. – Molly Picon and Jacob Kalich in my last years. – The sum of everything that you can’t go back and do again.

The closer I get to the end of my memoirs, I feel all the more as though I’m moving farther and farther away from the best years of my life – my best years on the Yiddish stage in America.

60 years on the stage is no small thing, after all!

When I began acting, I was a young man of 16. And now I am already, boruch hashem, a Jew of 77 years, and soon in April1 - if I make it to then in good health - I will turn 78.

Yes, 60 years on the Yiddish stage in America - that is no small thing.

With whom have I not played with on the stage! With the biggest and the smallest, with the best and the worst.

I got along with everyone. And if there was someone along the way who I got on poorly with, well, that mostly wasn’t my fault.

At the start of the 1927 season, I was engaged to play in the New York Public Theater, and I was promised that I would be the first comedian. In other words, I would play the lead comic roles in the plays I performed in. There were two managers of the theater, Louie Goldberg and Nathan Schulman, both honorable men and good managers who knew who to run a theater. They put together a very good troupe, and the “star” who played the lead roles was Leon Blank. Aside from Blank and I in the troupe, there was also Samuel Goldenburg and Charles Nathanson.

But a short time before the season started, on one fine morning, that told us the news that Ludwig Satz had also been engaged to play in the Public Theater. I confess, when I heard this news I wasn’t too happy because having Satz on board meant that I would no longer be able to play the lead comic roles.

To take the audiences by storm right from the beginning, we opened the season with an operetta whose name I don’t remember anymore2. But I do remember that the operetta was staged so that the two “stars” Leon Blank and Ludwig Satz wouldn’t feel slighted and neither would eclipse the other.

The first two weeks were a huge success, and we brought in a lot of money at the box office. Goldberg himself said at the time that he didn’t remember a time in the Yiddish theater when they made this much money in just one week’s time. We thought that if the first week was so good, surely it would only get better. But then the second week came, and the operetta was such a failure that if we didn’t get it off the stage immediately we’d be doomed, and it would be hard to get out from under it.

So they quickly bought Libin’s play Kinder Fargesn Nit, and to be sure, just as quickly as we started rehearsals, the two lead roles were given to the two “stars” of the theater - Blank and Satz. The lead female role was given to Annie Meltzer, and she played it very well.

Two days before the first performance, Leon Blank suddenly became ill, and it was impossible for him to perform. He asked if they could push the performance back a week, but Louie Goldberg had no interest in doing that. Instead, right on the spot, he switched up the roles: he gave Blank’s role to Satz, and he gave Satz’s role to me.

Nu, it goes without saying that we had to do what the manager wanted. And even though we had to change things around in a great hurry, it didn’t go poorly: I quickly switched gears to play Satz’s role, and not only did the audiences love my performance, but the critics did too. As for Satz, he was so good in Blank’s role that no other actor could have done a better job.

In my opinion, this was one of the best characters that Satz ever created on the Yiddish stage. He played the role so well that after his performance, it was dangerous for other actors to play the same role because none of them - even the best - could live up to what Satz had created.

And of course, as soon as Blank got wind of what a splash Satz had made in his role, he couldn’t rest any longer. On Saturday night, he called the theater telephone to say that he was feeling better and was back in good health, and the following week he would return to play his role and they should announce it in the papers. When the theater managers heard this, they naturally were not thrilled, but there was nothing they could do about it. When we performed the play the next week, it was nowhere near as good because Blank wasn’t good in the role that Satz had played, and Satz wasn’t as good in the role that I had played the previous week…

The first switch was good, but the second switch was bad, and Libin’s play suffered a lot as a consequence.

When Kinder Fargesn Nit was taken down, we put on William Segal’s operetta Dem Rabin’s Zondele, with lyrics by Nachum Stutchkoff and music by Herman Wohl. And with this performance, something happened that was very characteristic of “starism”:

Satz, one of the two “stars” in the troupe, had to direct the play. He was given the play and told to learn it well at home, and then come back to the theater with it and lead rehearsals. But while he had the play in his hands for a few days, he cut parts out so that he would take center stage the whole time, singing every song with lines in every scene. And we, the other actors in the troupe, would just rotate on the stage so that all the action was centered on him.

When the actors in the troupe heard about this, they were all terribly offended. We all went to Louie Goldberg and said that Ludwig Satz might indeed be a “star,” but we’re not going to put up with this - in other words, we are not his assistants. We too are actors, and when we put on a new piece, we don’t do it just to prop up Satz, but so we ourselves can perform.

The manager realized that we were correct, and he took the piece Dem Rabin’s Zondele from Satz and gave it to Samuel Rosenstein to direct. But when Satz heard this, he became angry and said that if he didn’t direct it, he would not perform it in either.

A series of messages were passed back and forth until Satz, with great difficulty, was persuaded to direct with piece together with Samuel Rosenstein and not cut parts of the piece and leave the other actors with nothing to do…

This was all in the year 19283, and I recounted this story because it is so typical of the “starism” in our little Yiddish theater world that had gotten even worse than before, after Aaron Lebedeff changed the game with his play Liovke Molodietz.

In those days, Molly Picon and Jacob Kalich had become big names. Molly truly reigned on the Yiddish staged. Every operetta she performed in was hugely successful. The Second Avenue Theater where she played was the center of the scene, and not only did the regular folks attend but also the intelligentsia who were well educated in Yiddish theater and literature.

When the theater managers approached me to ask if I would come over to join the Second Avenue Theater troupe and play with Molly Picon, I accepted their offer with great pleasure. During negotiations, Jacob Kalich told me that he wanted me to perform without any makeup and instead to perform just as I am - with a smooth, clean-shaven face and a white head of hair.

Everyone agreed on that.

And over the three seasons that I played with Molly Picon - two seasons at the Second Avenue Theater and one season at the Folks Theater - I played just as I am, with a smooth face and a white head of hair4. And I feel it’s necessary to mention that both Molly Picon and Jacob Kalich treated me so well the whole time that it really couldn’t have been better. They couldn’t have taken better care of me if I were their own brother, or even their own father. Willy Pasternak and Nathan Parnes - “The Boys”5 from management, as we used to call them - were also good to me.

As with all the others who were good to me over the years I’ve been on the Yiddish stage, I also thank Molly Picon and Jacob Kalich from the bottom of my heart. They were the last managers I worked under over my long career of sixty years. They were my last managers, and also my good friends. And since there is no longer a Molly Picon Theater, I go around like one of those “wandering stars,” and from time to time, when people remember me, I still perform somewhere, and always without makeup - with only a smooth face and a head of white hair…

Writing these memoirs has brought me closer to the wider Jewish community which I have always loved. While writing, I remembered a lot of bad things that I had forgotten, and also a lot of good things that came to my mind quite often. But there’s no harm in telling both the bad and the good when recounting the entirety of a career on the stage. And believe me, if I could, I would do it all over again. It wouldn’t even bother me to stand on a street corner in Philadelphia and shout at the top of my lungs, “Parlor matches, two for five! Parlor matches, two for five!”, 6 just like I did some 60 years ago when I came to America as a young man with my mother Feige the Possessorka and “made a living” from selling matches in the street…

It was a long way. It was a hard way. But…

But oh, if only we go back and do it all again!

.ענדע7

April 1947, a little under 2 months after this final installment was published↩︎

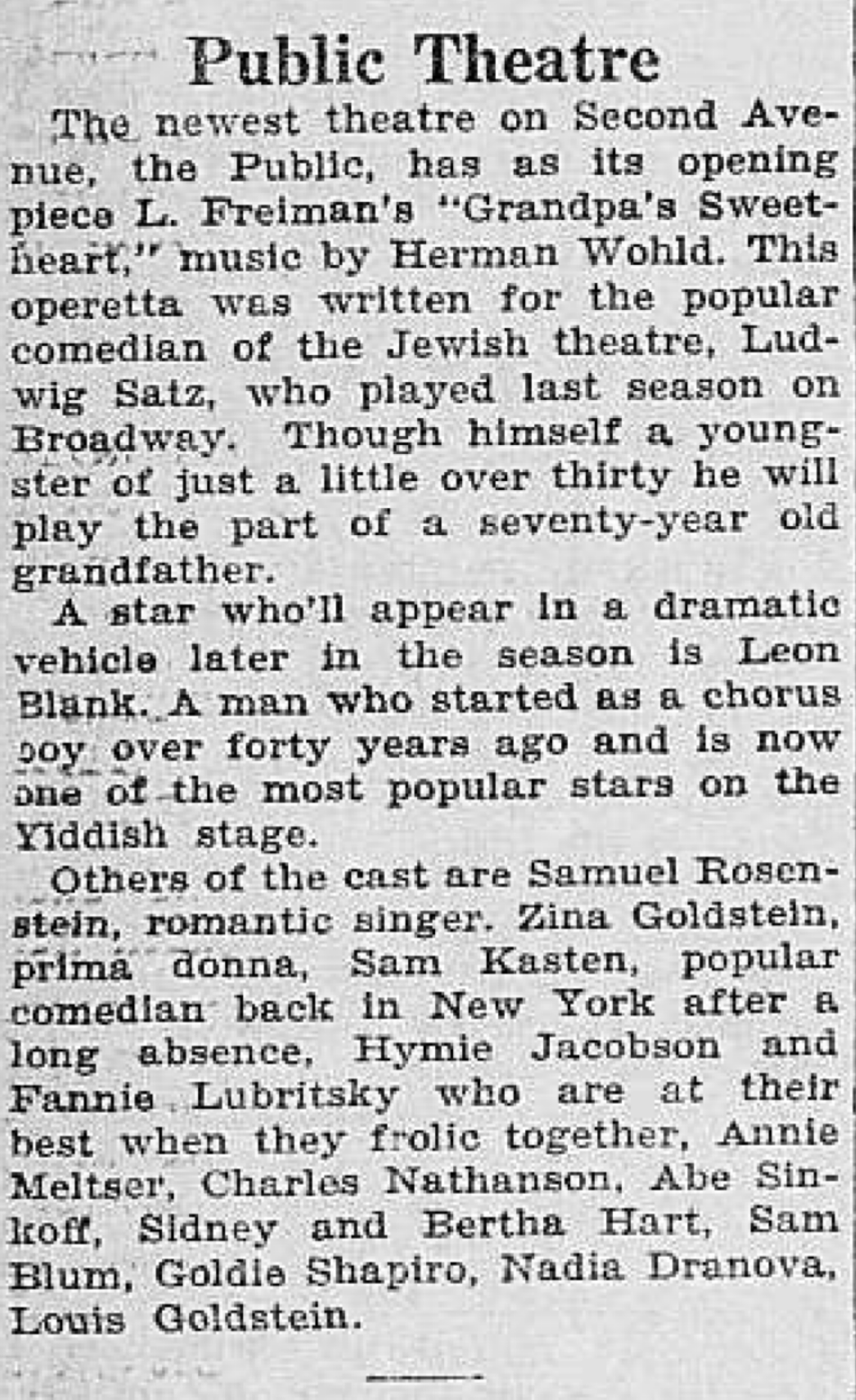

According to this advertisement in Forverts from September 21st 1927, the operetta was Dem Zeyden’s Gelibte. An article about Ludwig Satz’s performance in the show entitled “Ludwig Satz, Popular Yiddish Comedian, Shows Rare Ability As Star in New Musical Operetta” appeared in the Brooklyn Sunday Star on November 6th 1927. Sam is pictured on the bottom right of the cartoon in the advertisement, and he is described Sam as follows:

↩︎Sam Kasten is another artist of old school. He takes advantage of a very small and unimportant role and creates laughter and applause, where another actor in his place would feel lost alongside a comedian like Satz. However, the two work in perfect harmony and carry the production on their shoulders.

the 1927/28 season↩︎

He performed with Molly Picon and Jacob Kalich through the 1930/31 season when he was 62 years old↩︎

די באָיס↩︎

It’s worth noting he originally recounted this as “three for five” back in Chapters 5 and 6.↩︎

The End.↩︎