26 Performing in the People’s Theater

Published in the Forverts on December 14th, 1946

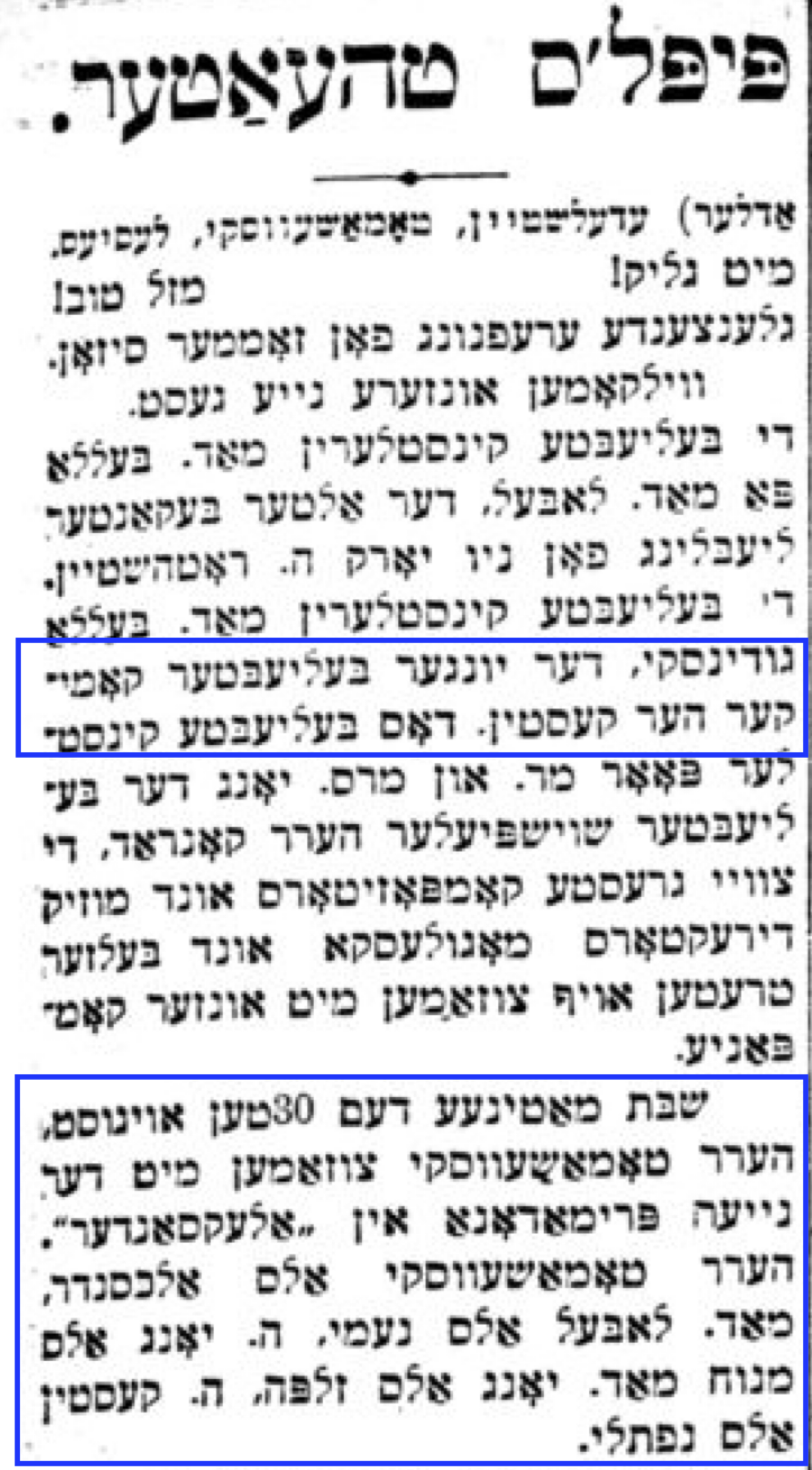

The fear that theater fans had of roles belonging to the comedian Berl Bernstein. – Bessie Thomashefsky in trousers. – Yosl Edelstein during the time when Mogulesko lost his voice.

Beginning the season1 in the People’s Theater, we put on Lateiner’s operetta Aleksander, oder der Kroynprints fun Yerusholayim. Boris Thomashefsky was always a big hit in the role of the crown prince. In the play, I performed the role of Naftali the Mishuganer, who speaks to himself that the true crown prince is him alone.

This was a role that the comedian Berl Bernstein had held for a long time. He played this role many times in New York, and the audiences really loved him as Naftali the Mishuganer. As such, he had a lot of fans who were ready to walk through fire and water for him. So, among them there was suddenly a behole2 - How could they give Berl Bernstein’s role to Kasten?! Who even is he, this Kasten?! And how could he possibly compare to Berl Bernstein in this role?! How could they do this to Berl Bernstein’s legacy, to let Kasten take the stage in this role?!

These fans really thought they were in the right. It’s not an exaggeration to say that, in those times, the Yiddish theater audiences really held an actor’s fate in their hands. When an actor was in need, they completely devoted themselves to him, and there was nothing that they wouldn’t do for him. If you ever dared to utter a bad word about their liebling, they were ready to rip you to shreds.

The famous Yiddish actors like Jacob P. Adler, David Kessler, Boris Thomashefsky, and also Berl Bernstein all had these sort of fans who were ready to stick up for them. These fans didn’t want to suffer me being given Bernstein’s role in the People’s Theater…

They really fumed over this and worked themselves up, and they told us that, having thoroughly discussed the whole matter, they would all come to the first performance and watch me perform the entire role, and here’s how it would go: They would let me perform the role of Naftali the Mishuganer if I played it in a new way, different from how Bernstein would play it. But if I did not play the role differently and played it just as Bernstein would, then there would be hell to pay. They would make a huge scene in the theater and pelt me with rotten apples, and they would make sure that I would have no choice but to get off the stage…

In hearing this, I thought - this could have been worse, and I suddenly stumbled upon an ingenious idea. The idea was that, before the curtains went up for the first show, I saw to it that the two trees which are part of the set would be well screwed to the stageboards, as strongly as possible. And when the scene came where Thomashefsky, in the role of the Crown Prince Alexander, challenged me to a sword fight, I would jump up into one of the trees. And when he came at me with his sword, I would jump to the other tree in one leap, and I would do it so cleverly that Thomashefsky would be left standing in confusion, looking around in all directions, and he’d call out:

– You mumzer3 how did you do that…?

Jumping so quickly into one tree, and then from one tree to the other, is something Berl Bernstein could not do, because he was too heavy. But I was weighed much less - a little squirrel who could flit around, and very light on my feet. It wasn’t hard for me to pull off this little stunt. I did it like a real acrobat who was skilled at this sort of thing, and I was such a hit with Bernstein’s fans that they didn’t think about driving me off the stage anymore. I passed their test, and everything was good and fine.

And that’s how I got “in” with the fans, who held an actor’s fate on the stage in their very hands. Afterwards, I performed many more plays in that theater, and a lot of those fans stuck with me and became my own admirers.

In those days, in most plays that were put on in the People’s Theater, Bessie Thomashefsky did not play roles of young girls or women, but instead only roles of boys or nimble young men. This was customary. And the audiences knew that Bessie Thomashefsky - an actress with true talent who God had blessed with a lot of charm - usually played in trousers4

But once, when we began rehearsals for some new play, they gave me the role of an agile young man, and it was a big surprise to everyone in the troupe, because they were sure that of course Bessie Thomashefsky would play this role. Boris Thomashefsky gave me the role simply because, at the time, he was mad at Bessie. Their sholem bais5 was beginning to break down, and he wanted to show her that he was the head of the household and he can do what he wants. But it wasn’t my place to interfere in such matters; they gave me a role to play, and I would play it. They gave me a song to sing in the role, and I would sing it. The politics around it didn’t concern me.

But after a little time passed, Thomashefsky made up with Bessie, and then straight away he gave her a role in the play - the role of the young man, as was customary for Bessie Thomashefsky to play.

But the real victim of this situation was the actor Louis Birnbaum; he was also cast in the role of a really lively young boy, but they took the role from him and gave it to Bessie. And then it got worse - they took my song and gave it to her too. And this really annoyed me, because I was a big hit with audiences with this song. And I really loved the song, too.

But what could I do? I had no real authority in the theater, and I knew that if I complained, it wouldn’t make a difference. I reasoned that nothing would change this decision, and I confess that I was really hurt by it, and I was ashamed of that. And then Edelstein, the sullen man Edelstein, learned what had happened, and he, who was usually more quiet than talkative, suddenly became vocal and he firmly said:

– We don’t play these kind of games in my theater! I will not allow people to be insulted like this! This will not stand!…

His opinion was that that giving an actor a role and then taking it away to give to someone else was something only the directory of the theater should do. If the directory thought that someone else would play the role better, then he could reassign the role to them. But to take a song that is part of an actor’s role away and give it to someone else to sing - this was not acceptable!…

– No, I say, in my theater we will not play these games! - Edelstein spoke loudly and sharply. -I will not allow people to be insulted like this!…

And he saw to it that the song was given back to me, as he wanted, and I would sing it in my role just as before. Yosl Edelstein had a strong sense of justice, in his own quiet way. He kept his eye on everyone and everything. And just like he hated being deceived by those who thought they were so smart, he hated deceiving others. He marched to the beat of his own drum6. And he was no pushover. He knew what he wanted, even if he didn’t say it out loud.

It’s worth sharing another anecdote that is very characteristic of Edelstein’s relationship with the actors. In that season I played in People’s Theater, the great Yiddish artist Mogulesko fell ill and rumors started circulating that he would never be able to perform again. The great artist who had enchanted thousands and thousands of people had lost his voice. He couldn’t even utter a single word. He fell into a deep depression, sitting at home alone for hours on end, vacantly staring out the window at the street as people walked, preoccupied with their business or their pleasures. He heaved a sigh, and who knows what kinds of thoughts he had going around in his mind.

Very often, when it seemed to him that he was disturbing his wife and children with his silence and his sickness, as though an evil spirit had possessed him, he would go out alone to the park. And just like he would do at home, he would sit, pensive and preoccupied. When some passerby would ask him something, he was unable to answer because he had lost his voice and could not utter even one word. He felt embarrassed, ashamed as a child who was caught doing something not nice. And this is how he - the great artist, who did not know how great he was and what a deep mark he had made on the Yiddish stage - passed the time, tormented and tortured. And in his despair, he thought that maybe it would be this way forever, that might never again play on the stage and of course everyone would forget him…

In those times, the most difficult of Mogulesko’s life in America, Edelstein sent him $25 every week… And he didn’t have to do anything to earn it.

But Mogulesko did not like being given money for nothing, so from time to time he would come to the People’s Theater, and tapping one finger on the piano, he would study the music with the actors who had to sing songs in their roles. It was heart-wrenching to watch him do this. Your heart simply ached watching it. The great Mogulesko - who could not speak even one word! The genial comedian Mogulesko - without even smile on his face!

And rumors spread that he intended to play the drums and be a percussionist in the theater orchestra…

It was not only us, the actors, who worried about Mogulesko. Indeed, the wider Jewish community was concerned. It wasn’t anything new that a Jew would stop someone from the theater community in the street just to ask them, “How is Mogulesko?” He didn’t want to know anything else. He didn’t want to ask anything else. And when he got the answer that things were not good with Mogulesko, he would shake his head and say, “May God have mercy on him. We must pray for him.”

There was no other Yiddish performer that the people - the regular/“everyday” people - showed such great interest in and had such abiding love for as Mogulesko. The intelligentsia circles, where people held debates about literature and art, also showed great interest in Mogulesko, and they all wanted to know if there was any hope that he would regain his voice and be able to perform again.

People were looking out for a miracle. People were waiting for it…

1902/1903↩︎

a panic/chaos/uproar↩︎

bastard; here, used figuratively as we would in English↩︎

as in, she played boys’ or men’s roles.↩︎

Literally means “peaceful home,” and implies domestic harmony within the family/between spouses↩︎

I’ve used this idiom where Sam writes, “he had his own way in life.”↩︎