4 From cheder to cheder

Published in the Forverts on September 25th, 1946

Tate’s death shook our entire family to the core, and nothing could ever be as it was again. No matter how hard mame worked so that we would not be in need or have to ask for help, it was never enough. The name “Feige the Possessorka” began to sound like a joke, because a possessor is a professional with means to live well.

When mame lost all interest in running the possessiye , she left Zatishiye and moved to the shtetl of Rybinka where my sister Bas-Sheyva lived with her husband. In Rybinka, we opened what is called a parnose shtieb1 where they sell everything that you can think of - even a little drink.

Mame worked very hard in the parnose shtieb and she was really a great eyshes-chayil2 and knew how to get along with people - not only with the Jewish customers who bought various small things from us but also with the goyishe customers. She understood who could be given a loan, and who could not. Her business acumen earned her respect and authority, and people still called her “Feige the Possessorka.”

A possessorka without a possessiye3.

Mame couldn’t figure out what to do with me. She was of course sure that a woman - a widow no less - could raise her daughters well enough for people to see them as fine and respectable children. But with a son, it was more difficult. Especially with a son who was a little spoiled and didn’t show any great desire to learn…

Just like tate, mame also wanted me to grow up to be a mentsh and to study at least a little, if not a lot. She therefore sent me to Belaya Tserkov to join the cheder of the melamed Chaim Machaliyes. She had heard he was a very good melamed whom children of the finest and most honorable families studied under.

“Look, Shmuel’ik,” she announced to me. “Put your head down and study, and you will be a scholar. A Jewish boy must be able to learn.”

During my time in Belaya Tserkov, I lived with Shmuel Pekelis4, my brother Itzhik Gedolia’s father-in-law. Shmuel Pekelis himself promised to watch over me like his own child and that I’d be well cared for. They did take good care of me, but the trouble was, because I was an orphan5, I was watched over a little too closely. I only had to do one tiny thing and I’d be immediately reprimanded for it: “This is not acceptable, Shmuel’ik. Not acceptable. Your mother is doing everything so you can be in this cheder, and this is how you repay her!”

The truth is, I wasn’t really a mischevious or insolent boy. On the contrary, I was actually a quiet boy, and I didn’t draw too much attention to myself. I always kept myself very clean and neat. Whenever someone gave me a new outfit, my eyes really lit up. I preserved it so it always looked brand new, as if it had come straight off the needle. I also had a tendency to sing every song that I heard in the street. As soon I heard it, I was immediately singing it. And you could dance to the song, I danced to it too.

But all the people who were watching me under a magnifying glass didn’t want me behaving this way, so they scolded me, “What is the big deal with you? What are you doing, dancing out of nowhere like that?” Sometimes they also brought up that I am an orphan…

Orphans are forbidden from singing. Orphans are forbidden from being happy.

My brother Itzhik Gedolia, nicknamed Kotik because he was as quiet as a kitten, used to come from time to time to Belaya Tserkov from the village of Solovinke where he lived and sold grain. He also scolded me and lectured me that I should behave so that everyone, including his inlaws, could say that I was just as quiet as he was.

In the end, it was all too much for me, and I couldn’t take it anymore. I also longed for my mother very much, so I begged him, “Do me a favor and take me back home. I’ve been here enough. I can’t stay here any longer. I’d rather go to the cheder in Rybinka.”

I also asked mame to let me come home. When they finally gave in and let me go back to Rybinka to live with her again, I was sent to cheder with the local melamed Shmuel Yossel. This alone took away any joy I might have had from being home. Nothing good could come from this man.

He was an angry Jew, Shmuel Yossel. A Jew with a red beard, a broad physique, and with two large, glaring eyes. He did not know how to speak to a student with kindness. He was always angry, and the anger always simmered in him just like in a cauldron. And when his two big glaring eyes focused in on you, you felt them pierce your soul6 and you were overcome with terror.

Though I wanted to keep my promise to mame to study well in the cheder in Rybinka, I was unable to do so. It was absolutely impossible to learn anything from such a melamed. We all hated him in the cheder. His wife too, who sold apples in the market, hated him like a spider7. Her hatred towards him was not unfounded. Hardly a day went by that he did not beat her. When he hit her, she screamed with a voice as if possessed, “Save me, Jewish children! He is going to kill me, the murderer…!” Of course, I could not learn much Toire from such a melamed. Every day in the cheder was a punishment for me.

There is something in particular I remember from those days that is vividly imprinted in my memory, and I’d like to share it here. It was on a hot summer day, soon after lunch. Suddenly there was something like a stampdede through the shtetl. When Reb Shmuel Yossel went outside to see what was happening, he immediately ran back inside and shouted loudly: “Come, shkotsim8, with me!”

In a hurry, he grabbed his kaftan and ran out, and we all ran out after him wondering where he was taking us, afraid of where it would be. We followed him, none of us saying a single word, to the besmedresh9 where we saw something I will never forget.

In the middle of a group of inflamed and angry Jews stood a frightened man, Meïr the meshoyrer10, who in those days use to daven on Shabbes at the cantor’s podium in a nearby shtetl. We all knew who he was, because he was the Rokinter11 rabbi’s son, and his brother Yehiel was the Rybinker shoychet12. He was a very nice young man, Meïr, and he always acted as though there was nothing to fear in the world. But now, he stood there stunned, trembling with terror, while a group of enraged Jews shouted at him and called him horrible names. One angry Jew slapped him across the face.

“You scoundrel!” they screamed. “You oycher yisro’el13!”

But this was not enough for them, so they also forced him down and gave him a real lashing. There was no use fighting them off. Meïr couldn’t take on so many people and had to accept the beating.

What Meïr did to receive such punishment I didn’t know. The other students in Shmuel Yossel’s cheder did not know either. Only after he was released and handed over to his brother Yehiel did we find out that he was accused of very a serious sin, a sin against God, along with his friend Leibish. That’s what they said in the shtetl. He was already starting to assimilate and heading “off the derekh”14. Leibish should have gotten the same lashing as Meïr, but he ran away and nobody knew where he went.

Meanwhile, everyone in shtetl lost their minds. Everywhere you looked, people were talking about it. And Reb Shmuel Yossel was in seventh heaven15. He never missed an opportunity to remind us what we saw that day: “Nu, shkotsim,” he said, stroking his red beard. “Nu, shkotsim, have you seen what happens to an innocent young man when he commits a sin against God? Eh?… That’s exactly how you will be beaten and cut off, when you commit a sin against God…” This is why he had led all of us to the besmedresh: He wanted us to see the punishment with our own eyes so we’d remember it…

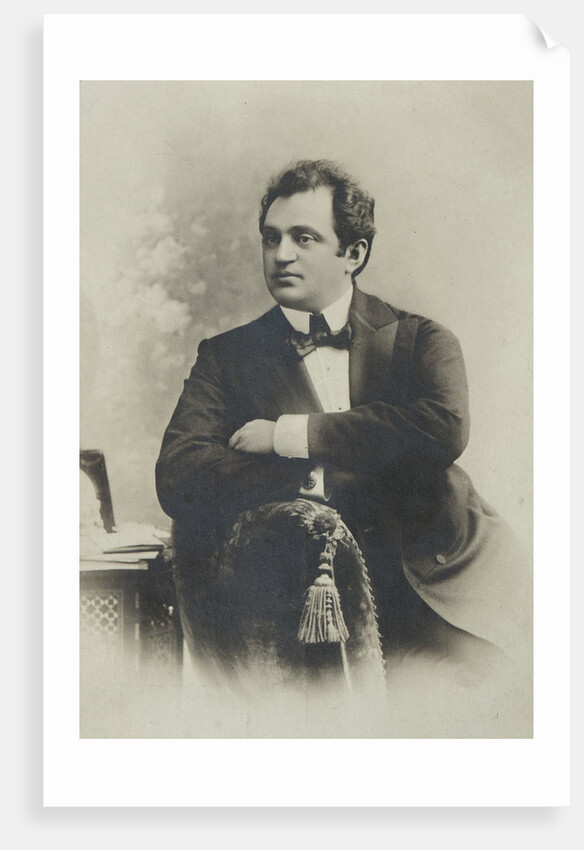

After that, Meïr was too ashamed to show his face in the street; he left Rybinka, and he never came back there again… But heard of him again? Yes, indeed we heard a lot because he, Meïr the meshoyrer, son of the Rybinker Rabbi, later became a famous opera singer on the Russian stage. And he called himself Medvedev16…

But he never forgot that day when when they beat him in the besmedresh. And when I met him again many years later in America, we both laughed about it. But I will tell you more about that later17…

Literally translates to “livelihood house”; פרנסה שטוב↩︎

“woman of valor”; essentially, embodies the ideal of a Jewish woman↩︎

“A farmer without a farm.”↩︎

Again, his name was probably not Shmuel but Isaiah-Leyb↩︎

Although his mother is alive, it was common to refer to children with deceased fathers as orphans.↩︎

The actual phrase Sam uses here is an idiom that is quite hard to translate: “you felt like he was curdling your mother’s milk”↩︎

presumably an idiom, she hates him like one hates spiders↩︎

pranksters, ”punks”↩︎

“Beit Midrash” meaning “house of study;” a place for dedicated Torah/Talmud study↩︎

choirboy in a synagogue↩︎

Butcher, and this is a highly respected position because butchers in Judaism are necessarily very learned due to their training in proper kosher slaughter.↩︎

derogatory term for someone who has greatly sinned, especially apostates, and brought shame on the Jewish people↩︎

Sam does not use this phrase, which is a more modern-day idiom. Instead, Sam writes that he is שוין ארויס לתרבות–רעה.↩︎

This is in fact a Jewish phrase/concept. In Judaism, there are seven levels of heaven.↩︎

Mikhail Efimovich Medvedev, né Meïr Haimovich/Yefimiovich(?) Bernshtein.↩︎

Specifically, in Chapter 22↩︎