33 Kessler pecks at seeds

Published in the Forverts on January 9th, 1947

Again in Philadelphia, and then back to New York. – With Kessler in rehearsals and the parables he told in disjointed and choppy words.

At the end of the second season in the Kalich Theater, we were told that next year there would be no more performances there because the building was being torn down to make way for the great bridge that would connect New York with Brooklyn - now the well-known “Manhattan Bridge.”

I was naturally very sorry that the Windsor Theater1 was being demolished - after all, I had made a name for myself there during the first few years I played in New York. And even to this day, when I walk past the Manhattan Bridge, I usually stop there for a moment. Somehow instinctively I pause, and I think to myself - once upon a time, the Windsor Theater stood here.

After the season2 ended, Anshel Schorr came to me with an offer to play in Philadelphia in Mike Thomashefsky’s Columbia Theater, and we agreed I would be paid $100/week. On top of that, they’d hire my wife as well and pay her $25/week. Mike Thomashefsky put together a troupe in Philadelphia of big-name actors, among whom was Schwartz, the same Maurice Schwartz who later created the Yiddish Art Theater. But at that time, no one imagined that one day he would create such great things for the Yiddish stage and that he would launch a new chapter in the history of Yiddish theater in America.

Generally speaking, the Yiddish theater in Philadelphia was nowhere near the level of New York and simply could not compete with it. In Philadelphia, they would put on the same plays that were popular in New York, and they played them like there really wasn’t anything to be ashamed of. It was common that a popular play would have a longer run in Philadelphia than in New York, and I remember how once, in Mike Thomashefsky’s Columbia Theater3, we put on A Mensch Zol Men Zeyn4, which Moishe Schorr5 and Anshel Schorr wrote together, for a record 25 weeks in a row. And we played it so well that the theater bigwigs even came down from New York to see us play it.

I played in Philadelphia for three seasons6. I achieved such renown that even people who remembered me well from the early days and called me “Samke” back when I was struggling to make a name for myself, started to call me “Mr. Kasten,” and I had many great fans among them.

But I still yearned to be back in New York, and when I was offered a job at the Thalia Theater7, I grabbed at it. At that time, there were three managers of the Thalia Theater - David Kessler, Boaz Young, and Max Wilner. Max Wilner, who was David Kessler’s second wife’s son, managed the business. He was jack of many trades and handled all aspects of the theater business, but he didn’t talk much. With a cigar in the corner of his mouth, he would sit around for hours and say only a few words, but that didn’t mean that he had nothing to say. On the contrary, he always had an opinion about everything, and also a well-thought out plan, and usually he’d see it through and make sure it all went as he wanted.

I always loved to work with David Kessler. But at the same time, I was also afraid of him because when he became capricious on the stage, or suddenly went in a rage over something, he was impossible to put up with. And when he would, in the middle of performing, start to growl his famous “No” from between his teeth with his own strange sort of sharp grunt, it freaked everyone out and completely disoriented them. I remember how one time I said to him:

– Listen, Mr. Kessler, if you start to growl “No” at me one more time on the stage, I’ll cause a scene!

– A scene? - He said, glaring back at me with his two great eyes. - Pray tell, what exactly, Kasey8, will you do?

– I’ll yell “fire!” on the stage! - I answered.

But really, I did love working with Kessler because he was a great artist who knew what he wanted, even if he couldn’t express it in words. And that’s why I jumped at the offer to join the Thalia Theater troupe where he, the great David Kessler, was one of the managers. Maurice Schwartz was also hired with me. Together, my wife9 and I were paid a total of $220/week. I don’t know how much they paid Schwartz…

While working out my contract, an amusing scene took place, and I have to tell you about it. I was in a restaurant on 2nd Avenue with Max Wilner on one side, and with Charlie Weinblatt - the son of the old Yiddish actor Yisroel Weinblatt who became a farmer10 and wanted his son Charlie to also be a farmer. Charlie didn’t want to be a farmer, but a lawyer, and he was usually involved in contract negotiation between actors and theater managers. He had a good sense of humor, and everyone always had good jokes to tell about their time with him, but no one told better jokes than Charlie Weinblatt himself.

So, the three of us were sitting around haggling. Not only about the price, how much my wife and I would get paid a week, but also about how they would advertise me and how big my picture would be on the placards. All the kinds of things which are very important to actors… And every time Wilner tossed the cigar from one corner of his mouth to the other and said a few carefully considered words, I nudged Charlie with my foot under the table, to tell him to speak up for me and fight for a better deal.

It went on like this the whole time, but I didn’t know that, just as I was kicking Charlie, so was Wilner - he was also kicking Charlie under the table…

And suddenly Charlie Weinblatt, with a wide smile on his face, said to both me and Wilner:

– Now listen here, when you both stop kicking me under the table, I’ll know that everyone got what they wanted in the deal and both parties are satisfied… Take your feet off of me because when you kick me I can’t think straight…!

We all laughed at this, and afterwards Charlie Weinblatt himself told everyone in the theater circles about it, and they were all in stitches laughing about it.

The plan that Wilner made for kicking off the new season in the Thialia Theater was totally shot, because Adler beat us to the punch - he bought the Thalia Theater and became the new manager. Because of this, Kessler was suddenly left without a theater in New York - apparently just as Adler wanted. But Wilner found a solution about what to do with the whole troupe he had hired. He split the troupe in two and rented out the Lyric Theater in Brooklyn and the Liberty Theater in Brownsville, and we started the season with Joseph Lateiner’s piece Yom Hachupe11.

All at once we were playing in both theaters - in the Lyric Theater David Kessler played the lead role in the play, and in the Liberty Theater Kalmen Juvelier played the same lead role, and when needed, half of the troupe would go tour the provinces with Kessler. This was in the 191012 season, and I will never forget those times because, playing with Kessler, I had a lot of good times and also a lot of bad times. But I have forgotten the bad times and remembered only the good times…

No matter how hard it was to put up with Kessler’s caprices, it was worth it because he was one of the greatest actors who has ever appeared on our Yiddish stage. With his keen artistic sense, he was able to grasp things that no one else could. He had a world of imagination, but he lacked the right words to express it when speaking. Only through his acting, even without words, he could show how a role should be played, and it was a pleasure to watch him demonstrate in rehearsals how to play one role or another because in his imagination he was able to see it all so clearly. And even if he didn’t exactly understand his own role, he found a way through the unknown to create such a full character that you’d never forget.

It was perhaps Kessler’s great misfortune that his heyday on the Yiddish stage was in those days just when long monologues were the main thing. He wasn’t so good at those, because he was much more of a physical actor. His acting was more powerful without words than with, and on top of that he was far too impatient to memorize the sea of words in long monologues.

In the rehearsals he held with actors when preparing for a new piece, or even an old one, he used to tell such stories that it was no wonder that everyone would talk about them after. I remember one time in the Lyric Theater when we were rehearsing one of Gorky’s plays, he suddenly, is his own special way, launched into a whole discourse:

– What is a play? - He posed a question and soon answered it himself. - A play is…is - words! And what are the words that one performs in a play? The words are seeds which the actors gather up from the ground… Just like birds and doves peck at seeds… The seeds roll around on the ground, and you have to peck at them with your beaks and get a taste for them…Understand?

And with that, he finished the speech about the seeds. And when Kessler was not pleased with how an actor was playing a role in rehearsals, he’d usually grumble his famous “No,” which made everyone very nervous, and then he’d say:

– What do I want from you, eh? I want you to peck at the seeds…Like this: With your beak, just like a bird, pick up a seed and give it to me… You see!?… Just like that!…

And he would show the actor how to peck at the seed…

Also, when he himself would be in the middle of a performance on the stage, he would sometimes stand there saying nothing, because he really didn’t know the role, and between his teeth he would growl at the prompter:

– Gazlen13! Mumzer14! Give me a seed…

It was often difficult to perform with him. Difficult and yet pleasant, because he was such a great artist that he could get away with his caprices…

Recall, although the theater had been renamed to the Kalich theater, it was known before - and for a much longer time - as the Windsor↩︎

1906/1907↩︎

At 3rd and Green Sts↩︎

Sheet music for the title song of the play↩︎

Anshel Schorr’s brother. An actor and playwright, his Leksikon fun Yidishn Teater entry has not yet been translated, but it is available from Volume 4, page 2650.↩︎

- ↩︎

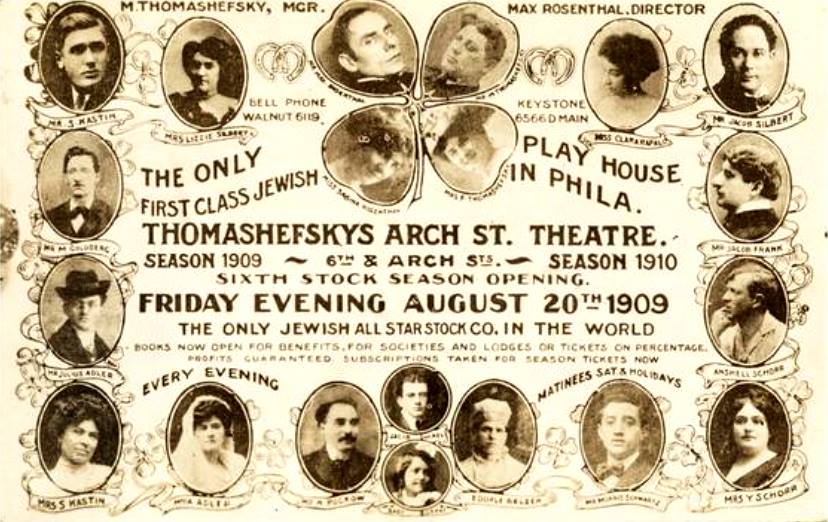

Sam played at the Columbia Theater during the 1907/1908 season, after which the troupe moved to the Arch Street Theater where he played during the 1908/1909 and 1909/1910 seasons. Below is pictured the Arch Street Theater troupe of 1909/1910, featuring Sam in the top left corner and his wife Suzie in the bottom left corner. There are several notable names here, including (but not limited to!) Sam’s old friend Jacob Frank (second from the top on the right side), Maurice Schwartz (second from the right on the bottom row), and Clara Rafalo whose career Sam helped launch in Cincinnati (Chapter 19; second from the right on the top row).

located at 46 Bowery↩︎

Kessler’s nickname for Sam Kestin↩︎

who apparently they also hired!↩︎

and bought Sam’s farm in ~1895↩︎

Listen to a song from the play↩︎

1910/1911↩︎

Slang effectively meaning “jerk.” Literally means thief/bandit↩︎

bastard↩︎