37 Toe to toe with Schildkraut

Published in the Forverts on January 23rd, 1947

An interesting story with Rudolph Schildkraut while performing Tolstoy’s Kroitzer Sonata.

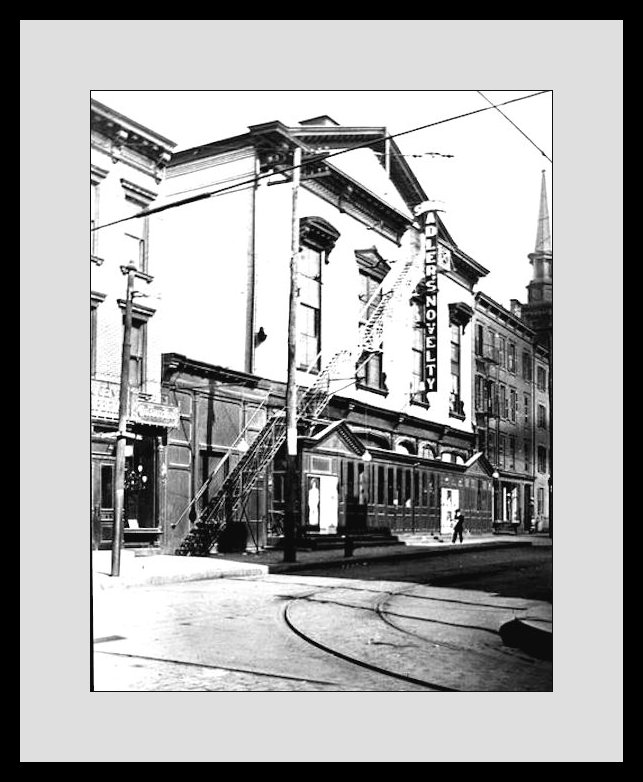

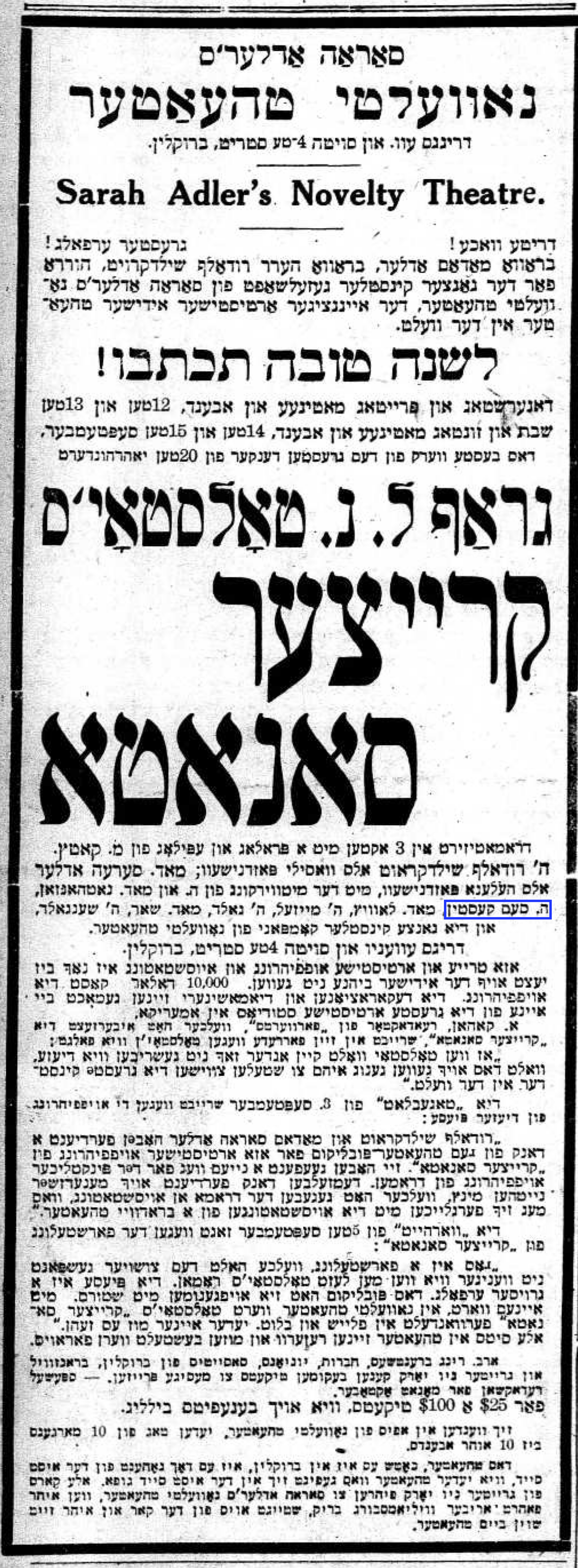

The Novelty Theater in Brooklyn, where I was hired to play in the troupe Sara Adler and Rudolph Schildkraut had put together1, was just like the story about how they built a new shul not because they needed one - but because the two gaboim couldn’t share the limelight in the same shul so they built a new one. For a change, Sara Adler was a little angry with her husband Jacob P. Adler. She wanted to show him that she could achieve great things on her own and that the audience valued her talent highly, so she went off and rented the Novelty Theater in Brooklyn - or better said, in some far off corner of Williamsburg.

To ensure her great success, she brought the famous Rudolph Schildkraut into her troupe. And you have to admit - you couldn’t have imagined a better combination, because both Sara Adler and Rudolph Schildkraut have graced the best stages in the world with their talent, and they have both excelled performing in the best pieces in the world. The mere fact that the first piece they put on in the Novelty Theater was Tolstoy’s Kroitzer Sonata showed just how talented they were.

We worked so hard in rehearsals that even in the Yiddish Art Theater no one ever worked harder. You see, Rudolph Schildkraut himself played the lead role, and because it was clear that the role was semi-autobiographical, Schildkraut played the part as though he weren’t merely playing a great Russian prince, but Tolstoy himself. He immersed himself in the role so completely that only such a God-blessed artist like Schildkraut could do. No one else could create such a full character.

Now, I’d like to say a few words about the difference between Kessler and Schildkraut. Not about their different acting styles, but about the different characters. They both had their fair share of caprices, as great artists usually do. But whereas Kessler was never able to restrain himself and when he was in a rage there was simply no holding him back, Schildkraut was a master at restraining his caprices. You could see this from how he behaved during rehearsals and on the stage.

During rehearsals, he never got angry or insulted anyone. Even when he had to work with another actor or actress of lesser talent, he never lost his temper, but he instead showed them how to perform the scene, over and over again. He never got sick of working with someone on a scene. But when he came across an actor who really did have talent, he was very happy and would usually say that, rest assured, they would “do good.”

He usually spoke in German when he directed us during rehearsals, so you might have thought that he doesn’t know a word of Yiddish. But while performing, he spoke the best Yiddish, and he had such a mastery of the language that it really was something to admire.

In general, he had a real knack for languages. He learned English in only a short time and played Shakespeare’s Shylock on the English stage, and he interpreted the character in such a way to make the Shylock, the Jew, the most sympathetic character on stage. He also performed pieces in Hebrew. We all marveled at the authentic, folksy Yiddish he spoke on stage. We also marveled at how well he read Peretz and what a master he was of all the Yiddish dialects.

But only on the stage - the second he came down from the stage, he went back to speaking in German.

Playing with Schildkraut was not only an honor, but a pleasure. You could always learn something from him while playing with him. He would often, while performing, invent character traits for his roles right there on the spot, making the characters he was portraying feel much more realistic. And still to this day, my heart and soul grow warm and light when I recall that, among the great Yiddish actors with whom I appeared on the Yiddish stage during all the years I’ve been playing Yiddish theater, one of them was Rudolph Schildkraut.

Around the other actors in the troupe, he acted in such a way that you could forget he was a world-renowned artist. He behaved as though he was no more than just a regular member of the troupe. He behaved simply and ordinarily; he was a good, beloved colleague.

I will never forget how he worked to prepare for his role in Tolstoy’s Kroitzer Sonata. He studied his role of the protagonist so well, and he came to know the role just as one knows a close friend. He uncovered every little trait there was to find about his character.

Sara Adler also worked very diligently preparing her role, and she played it very well. All the critics said so. And when her husband Jacob P. Adler came to see her perform, he too really enjoyed how she played her role. Their estrangement did not prevent him from expressing his honest opinion. Either way, people in our circles didn’t really take their estrangement seriously, and everyone knew that, just like they had done before, they would surely reconcile and there would be peace between them again…

I was given the role of the servant Igor in Tolstoy’s play. I loved this role very much, because to me, Igor was a very sympathetic mentshl, a depressed and unhappy man, who was always ready to serve because that was his place. I always truly enjoyed playing this role alongside Schildkraut. Every time he gave me positive feedback about how I played Igor, I was simply over the moon.

And now, I would like to share an interesting story which is very characteristic of Schildkraut the artist:

In the second act of Tolstoy’s Kroitzer Sonata, there was a scene where the nobleman calls for his servant, shouting:

– Igor! Igor!

I was supposed to come out onto the stage after the second time my character’s name was called, and upon my arrival, I was supposed to look frightened and shaken.

But one time, I just didn’t hear when Rudolph Schildkraut, while playing the role of the Russian nobleman, called out his servant Igor’s name for the second time, so I didn’t go out onto the stage in time. This sent Schildkraut into a wild rage, and he began screaming loudly as though he was possessed:

– Igor! Igor! Igor!

And when I finally came out onto the stage, frightened and shaken, Schildkraut slapped me across the cheek. And not just any slap, but a real good slap - a genuine slap…

He wasn’t supposed to slap me in the play. But he was so angry that I had missed my cue that he simply couldn’t control himself, so he slapped me anyways. But soon, he realized that this was not nice of him, and he felt very sorry for what he had done. But there was no taking it back. He suddenly fell to his knees in before me, and his eyes became full of tears:

– Forgive me, Igor! Forgive me, my dear man!… I didn’t mean it…I swear to you, I didn’t mean it..!

And he did this in such a way that it the scene really came out quite touching and emotional - so touching and emotional that the whole audience in the theater was inspired, and everyone began applauding. Indeed, it turned out to be one of the strongest scenes in the entire performance. And the audience thought that it was supposed to be played that way - that we performed it exactly as it was written in the play… It didn’t occur to anyone that how the scene went was not at all how it was supposed to go, but that in fact it was really a scene between me and the great artist Rudolph Schildkraut, who got down on his knees before me and begged me to forgive him for getting so flustered on stage that he slapped me - a real slap - for missing my cue.

After we finished playing the act, Schildkraut came to me backstage. Speaking in German as he always did offstage, he again begged me to forgive him. He was deeply apologetic and assured me that he was eating himself alive over what he had done. He asked me several times if I was actually hurt. And suddenly a wide smile spread across his face. He looked me in the eyes and said that now it has to stay like this…

– What has to stay like this? - I replied.

– The scene where I slap you and fall to my knees…

And he started to enthusiastically talk about how wonderful and powerful and natural the scene turned out, how much the audience loved it, and how it completely fit the character of the Russian nobleman that Tolstoy had written in his piece Kroitzer Sonata.

– This is brilliant! - he kvelled. - This is wonderful!

Enthusiastically, he told me how the Russian nobleman in Tolstoy’s Kroitzer Sonata really would do such a thing as hit his servant in a moment of anger, but soon after regret it and fall to his knees and beg for forgiveness.

– This is really authentically Russian! Authentically Russian! - he was really delighted.

And so it was - from that day on, we played that scene in Tolstoy’s Kroitzer Sonata just as we played it in that performance: I would come onto the stage frightened after he called out Igor’s name several times, and then he would angrily slap me. He would then immediately regret what he had done and fall to his knees to beg my forgiveness, and I would forgive him…

Changing Schildkraut’s mind was absolutely impossible. He was so adamant about this that no one in the world could have convinced him otherwise. And every time we performed this scene together on stage, it was always so powerful and so artistic and made such an impression with the audience that it was no wonder that the theater shook with resounding applause2…

Interesting fun fact: Abba Schoengold’s son Joseph Schoengold was also in this troupe↩︎

Celia Adler also recounts a version of this story in her memoirs; search for “Kasten” on this website to find it.↩︎