30 Waiting for the last act

Published in the Forverts on December 28th, 1946

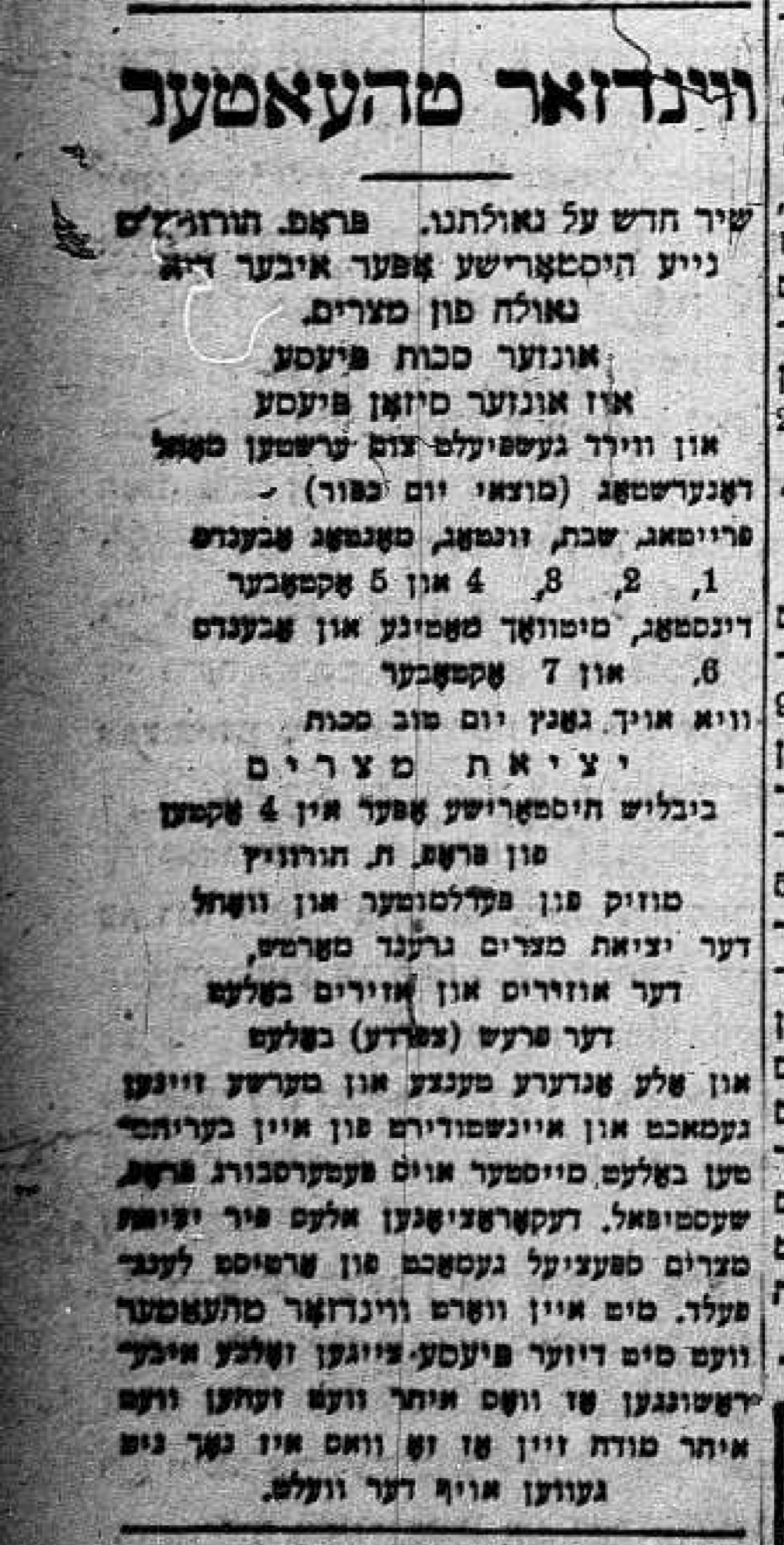

The curtain goes up on opening night, and the “Professor” still hasn’t written the last act. – Curiosities of the Yiddish theater of old.

Opening night arrived, and it was time to raise the curtains in the Windsor Theater to begin the performance of the historical operetta Yesties Mitsraïm, but the “Professor,” the genius who wrote plays fast as a baker makes rolls, had not finished writing the last act. None of the actors knew what would happen in the last act or what we were supposed to do…

Heine-Chaimovich, one of the managers of the Windsor Theater, was running all around in a panic, and angry with the “Professor”:

– You wretch, what are we doing to do? What will the actors do for the last act? How will we end the performance?!

The actors were also really nervous. Leon Blank was so beside himself that he was unable to articulate a clear word that anyone else could understand, so he just grumbled and groaned and threw his hands up in the air. Kalmen Juvelier tensed up his shoulders, and, like a lost wanderer, went from one person to another with a look on his face like he was pleading for something. Nobody could blame him, because God knows, it wasn’t his fault.

Shrage spun around and around like a shadow, looming larger and larger at each turn, and he would whisper something in your ear and then leave as though he were giving up all responsibility.

I tried to muster the strength to tell jokes, but my heart was heavy and dark.

The only one who was calm and didn’t take the whole situation to heart was the “Professor” himself. For all the grief we gave him, he had one response:

– You don’t have to worry. There will be a last act…

We, of course, thought he would have written the last act and given us direction on how to perform it by now, even though we wouldn’t have time to learn or rehearse it. We grew more and more nervous, and between acts, actors kept grabbing at pages from the “Professor” -

– Give us our roles! Let us learn our lines for the last act!

It went like this the whole time, until the curtain had to go up for the last act. When the chaos among the actors reached its peak, since none of us knew what was going to happen or how the play was going to end, the “Professor,” all calm and collected, said:

– Now, everyone go up onto the stage and line up in order!

We were shocked when we heard this. What would we do up there on the stage without a last act? What will we say when none of us has been given any lines…?

But when the “Professor” says to go up onto the stage, onto the stage you go. We all went up on stage and lined up in order. Standing there, we all exchanged glances - “What’s it going to be? What’s going to happen?”

And this is what happened…Yes, it happened just like this, something none of us expected:

As soon as the curtain went up, the “Professor” himself came onto the stage wearing a long white coat and a white beard he had attached to himself. He stood tall like a prophet or some kind of God-like figure, and raising one hand in the air he began to speak to Moishe Rabbeinu:

– Moishe, Moishe, take the Jews and lead them to the land where milk and honey flow, to the land of the cedars!

And he went on and on like this in his daytshmerish, and while speaking, he interspersed verses from the Toire, and then switched back to daytshmerish. He performed the whole last act by himself like a sort of epilogue to Yesties Mitsraïm itself. It was an endlessly long1 monologue, but he played it in a way that immediately won over the audience. He also brought us actors into it; he kept asking questions that we had to answer with a resounding “Yes!” And he ended with a bang that the audience loved. The curtains lowered, and the play was finally over.

This is how the “Professor” Moishe Ish Horowitz Halevy ended his operetta Yesties Mitsraïm, since he didn’t feel like or didn’t have time to actually write the last act. And we continued to perform the play exactly like this; even though it wasn’t entirely clear who the man in white was meant to portray, he gave Moishe Rabbeinu the order to lead the Jews to the land that flows with milk and honey, where the cedars grow… Was it a spirit? Or was it God himself? No real indication was given, and the “Professor” didn’t even really know. And when you asked the “Professor” about it, he usually gave the answer - “Don’t ask such questions…”

The same role - the role of the man in white - was later played by Leon Blank. And when he asked the “Professor” to give him the lines of the monologue, the “Professor” laughed:

– There aren’t any. - he said. - The monologue wasn’t written out. I just said whatever came to mind…

And this was the God’s honest truth. He just said whatever occurred to him on the spot. This was nothing new for him; he would often just go onto the stage to play a role in his own play, and when he did he didn’t say lines from a script - he just said whatever came to mind. This is what he did in play Tisa Esler2, where he played the role of the lawyer who defends the Jew accused of blood libel. He spoke entirely different lines at each performance, just as he did in his operetta Yesties Mitsraïm, for which he didn’t ever write the last act…

And when Blank asked if he could write out the same monologue that went over so well, he laughed again:

– Do you really think I remember what I said in the monologue?! I don’t remember a single word that I said…

He wrote a monologue for Blank anyways, but it was a whole other monologue entirely. Not at all the same words…

The operetta Yesties Mitsraïm was not a great success because, as I said earlier, in those times new winds were beginning to blow in the Yiddish theater. The sort of plays the “Professor” wrote were quickly going out of style, and nobody knew this better than he did. That’s why he tried so hard to make such a huge spectacle with this operetta, like using actual frogs when portraying the ten plagues, along with other special effects. But it didn’t help. The play was not a big hit.

But I was happy that we put on the play, as was Dora Weissman, because we danced together as a couple, which was not normally done in the Yiddish theater. We were both really pleased. The theater critics also gave us good reviews in the papers. If my memory serves me well, Abe Cahan, the editor of the Forverts, wrote that the “Professor”’s historical operetta was like a fur that you have no desire to wear because it’s certainly not fur you can pride yourself on. So, you put it away on a hanger worth more than the fur itself, the kind of hanger on which you’d hang a respectable fur that you can pride yourself on. This is also the case with the dance that Sam Kasten and Dora Weissman danced as a couple: It was the good sort of hanger you can hang a fur on - a fur that was certainly not one of the nicest.

This is more or less, if I remember correctly, what Abe Cahan wrote about the piece. He was delighted with my performance, you see, and I was really moved by it. The memory of this second season in New York, where I didn’t go downhill but instead I took my place on the Yiddish stage, really brings me a lot of joy.

Sam uses an interesting Yiddish idiom here: “long as the [Jewish] exile [from the land of Israel]”; לאַנג ווי דער גלות↩︎

A play (the first of two that Horowitz wrote about it) about the Tiszaeszlár affair, a blood libel trial in 1882 in Hungary↩︎