7 My first encounter with Mogulesko

Published in the Forverts on October 10th, 1946

I played an extra in no more than two or three performances with Heine-Chaimovich and Max Karp’s troupe. After that, they didn’t need me anymore and told me I could go home. As it usually went, they didn’t me pay for it. It didn’t even occur to me to ask to be paid.

In general, Yiddish troupes at that time would recruit local men and women to be “the folk” in the play1. In every city there were more than a few people who rushed to the stage for this, and were satisfied just to be so close to the great performers who they used to talk about with such enthusiasm. The stage drew them in like a magnet. And some of them actually became actors and actresses - and more than one of them made it to the top ranks and became famous…

In the shop where I worked as a shirt-maker, the spirit of Yiddish theater pervaded more than ever; there was no one who didn’t take the opportunity to go see the troupe who came from New York to Philadelphia for only a few performances. And since everyone knew I was on the stage with them, I was greatly exalted. They would request from me,

– Nu, Sam, how does that song go that they sing in that one scene? Nu, how?

And I didn’t make them beg, and I sang. And more than any other song, I sang "Rozhinkes mit Mandlen"2 I had to sing it for them several times a day, and everyone used to sing with me. And it started like this3:

In the synagogue, in a corner of a room,

Sits the widowed daughter of Zion, alone.

She rocks her only son, Yidele, to sleep

With a sweet lullaby.

And then everyone in the shop, amidst the noise of the machines, immediately joined in as though they were all “fully qualified”:

Ai-liu-liu-liu!

And so it went, just as if we were, here in the shop, putting on our own performance. And after the “ai-liu-liu”s were done, I continued:

Under Yidele’s cradle

Stands a small white goat,

Who went to market to sell his wares.

This will be Yidele’s calling, too.

Trading in raisins and almonds.

Sleep, Yidele, sleep!

Like this, all day long, I sang. And after the sung, everyone “licked their fingers”4 over it.

– Yes, that is good!

– Yes, that is sweet as sugar!

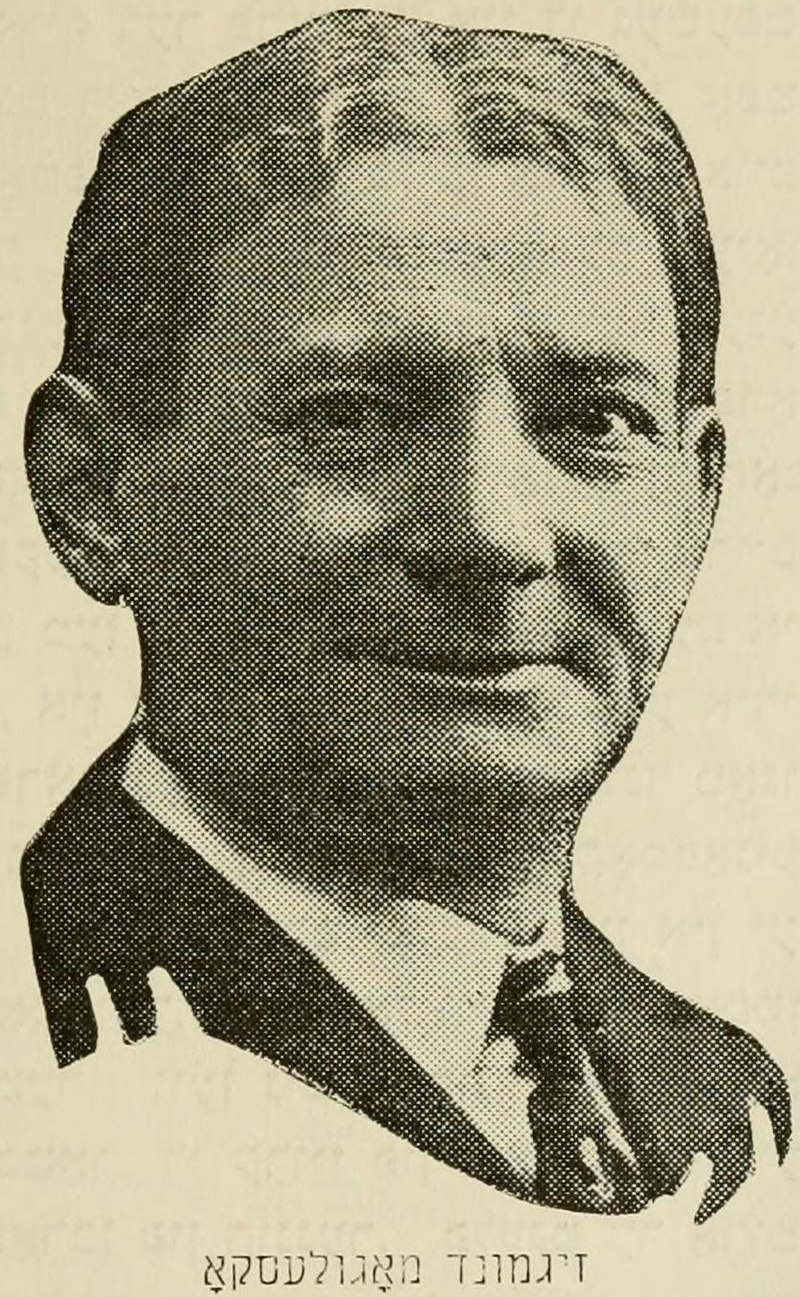

The spirit of the Yiddish theater filled the whole shop even more a little later when Mogulesko5, the great and famous Sigmond Mogulesko6, came to Philadelphia for a few performances. All of Philadelphia went crazy over this, and it was no wonder - like in many other cities in America, he already had many ardent and passionate fans before he even arrived. His fans were Ukrainian, Moldovan, and Romanian Jews who remembered him from back home.

They had seen him perform in Odessa, in Bucharest, in Iasi, and in many other cities in Europe. They couldn’t forget him, because even back in the old country, his acting inspired them, and when people talked about him, they said in the whole world there is no one better than him. When he performed in a theater, the voices of the crowd filled the air with great joy:

– Brava, Mogulesko! Brava, Mogulesko!

His talent spread like a rumor at those times, when Jews would come to see him play Yiddish theater in cities like Odessa and Iasi. It was in those times that the Yiddish theater was starting to pick up speed7.

Mogulesko came to Philadelphia to play the piece Di Kokete Damen8 where he could show himself in all his glory.9 He played the role of the libertine who later becomes old and broken and no longer recognizable. And in the same performance, he also appeared in the role of Bobe Shprintze10. And when he started singing the song "Yankele"11, everyone remained seated as if glued to their seats, and they swallowed every word and really kvelled from the song.

And Mogulesko performed the role of Bobe Shprintze with such grace and such charm, that it was no wonder that he enchanted the whole audience. Oh, how beautifully and how sweetly he sang!

My husband used to daven with twelve singers.

Ah, my dear Yankele!

Women used to lick their fingers12 from his singing.

My dear Yankele!

After his prayers we would run out of energy.

My dear Yankele!

Tell me, tell me, have you ever seen something like this?

No, no, no,

I was lucky to live to see it.

What a song Mogulesko sang - even when the words didn’t rhyme, it was such a pleasure to listen to him sing it that it didn’t matter. You really couldn’t believe it, how he charmed the audience with his artistic grace. You’d have to travel the whole world over to find another artist as good as him.

And I remember that when I saw him for the first time, in Philadelphia in the play Di Kokete Damen, I remained seated as though I had suddenly been transported to an entirely different world. And when the curtain fell and they turned the lights back on in the theater, I jumped up on stage and went behind the curtain.

I felt that I had to say something to him, the man who performed such wonders on the stage. I had to express my enthusiasm!13 I had to touch his hand! I had to thank him for the spiritual pleasure that he had given me.

This feeling gripped me so tightly that there was nothing I could do to escape it. I suddenly just forgot that, fundamentally, I have a reserved/shy nature, not like someone who elbows their way in somewhere. And when I went behind the curtain and said, that I had to see Mogulesko, they passed me from person to person. And it went on like this until a Jew14 loomed up from underground - a healthy Jew, a tall Jew, who spoke in such a way that you could immediately recognize he was Romanian; he told me to follow him, and while leading me, he shouted out loud:

– Hey, Zeligl15, some guy asked to see you…

And I still remember how strange it was to me, that this man used a nickname - for Mogulesko himself! - as though they were equals… He called him Zeligl…

When I was introduced to Mogulesko in his dressing room and I suddenly realized how near I was to him, I was left standing in a daze and I suddenly forgot everything that I had planned to say to him16. Only when Mogulesko stretched out his hand to me and I saw a good face, a kind face, I mustered the courage and I started to say,

– It is an honor for me, a great honor, to shake your head… I thank you…

He was, it seems, used to things like this, so he smiled, and then I became even bolder:

– And I tell you now, Mister Mogulesko, that I want to be actor just like you… I mean, I want to be actor.

Immediately after, I was shocked that I said that; it occurred to me that it was a chutzpe17 for me to have said something like, “Mogulesko is an actor, and I want to be an actor!” Who am I and what did I do?! And what does it mean that “I want”? Well, it means that is what I want!

But Mogulesko wasn’t offended by what I had said. “Good,” he replied. “This pleases me. And if you indeed become an actor, we will certainly see each other again…”

Then he became very busy and I could not spend any more time with him. As I was leaving, I shook his hand, and I wanted to say so much more to him, but I didn’t say anything…

At that time, neither of us could have imagined that, years later, I would play his roles on the Yiddish stage and he himself would say that I did not “embarrass” him18 and that he was pleased with me.

This was my first encounter with Mogulesko, the great and God-blessed artist, from whom I learned so much over the years while he lived and created great theater here in America. And this encounter took place in Philadelphia, a city which is so intimately linked with my career on the Yiddish stage. This meeting is so etched in memory, that now the whole scene is floating before my eyes. I could not forget what he said to me, that if I indeed become an actor, we will certainly see each other again.

And after he left Philadelphia, back in the stop here I worked, everyone already knew that I had the privilege to introduce myself to him and speak to him himself, so I was exalted and “crowned.” Everyone wanted to know what he said to me and what I said to him - not just the workers in the shop, but the boss himself was curious about this too. And I told them all about it. But the way I told it, I made it seem like I didn’t talk to Mogulesko for only a few minutes, but instead for hours and hours…

That’s how deep of an impression he left on me. And then everyone in the shop started singing "Yankele" which they sung more than any other song, and some of them wanted to sing it exactly as Mogulesko did. And when someone thought they wouldn’t be able to sing it like Mogulesko, they would turn to me and say,

– Nu, Sam, you show us how to sing it like Mogulesko does…

And I showed them, and they told me it was good.

We sang other songs from the play Di Kokete Damen too, in the shop in Philadelphia where I worked sewing shirts. And among the popular songs we used to sing, there was also the song "B’shtika"19 and as I recall, it went like this:

Who is that eating in the sukke?

And who is that fine man?

Thieves, swindlers, dreadful men,

What could be worse than them.

In everything, they act only with sechel20

And they steal in silence,

But you, my child, will be a mentsh,

You will eat in the sukke.

The song is composed of several people21. The song also makes fun of the of the “ultra-religious hypocrites” who pretend to be frum, but in reality they are not. The song also made fun of wealthy women, who cannot make good housewives. And it ended with a bang:

In silence, in silence,

will you eat in the sukke!

And indeed one more time:

In silence, in silence,

will you eat in the sukke!

That was the kind of song that was sung in the Yiddish theater in those days; a song the audience would immediately pick up and start singing everyone - at home and in the shop22. And it didn’t matter what kind of song it was, a good or a bad one - the song was always a Jewish song and it pulled at the Jewish people’s heartstrings…

If you need a hoard of commoners, get some locals to be extras!↩︎

“Raisins and Almonds”, a well known Yiddish lullaby originally from Shulamith.↩︎

You can find the full lyrics in English and transliterated Yiddish here.↩︎

idiom - they really enjoyed it, as in “finger-licking good”↩︎

This, and other bolded words, were bolded in the original article. In Yiddish, words are emphasized by spacing letters out; for example, this was actually written: “M o g u l e s k o.”↩︎

Nickname “Zelig;” he was the most beloved comedian of the early Yiddish theater, bar none. Read his Leksikon entry here. He and Sam would later become close friends, and Sam loved and admired him dearly.↩︎

it was the early days of Yiddish theater - it was catching on and becoming popular, bigger, etc.↩︎

From cross-referencing with Mogulesko’s Leksikon entry, we know this took place in 1887.↩︎

He made a serious impact playing this combination of roles over the years↩︎

You can find the full lyrics in Yiddish here, starting at the number

1.halfway down the page.↩︎idiom; “really enjoyed”↩︎

or, “how inspired I was”↩︎

It it worth noting that Yiddish speakers generally referred to fellows Jews as “Jew” rather than, here for example, “man”↩︎

Yiddish endearment nickname for Zelig↩︎

Sam literally wrote: “suddenly everything I was going to say before went out of my head”↩︎

audacity, insolence↩︎

Roles were often quite tied to the actor who originated them (not unlike today!). For example, when you played one of Mogulesko’s roles, your performance might reflect poorly on him as much as on you.↩︎

“In silence”. You can find the full lyrics in Yiddish here.↩︎

brains,common sense↩︎

As in, the song sings about several different people (in the subsequent verses)↩︎

as in, at work↩︎