34 Clashing with Kessler on stage

Published in the Forverts on January 11th, 1947

Good and bad moments while playing together with David Kessler. – Character traits of the great artist.

During the rehearsals with David Kessler in Brooklyn’s Lyric Theater while we were putting on Gorky’s play, Kessler was harder on Schwartz1 than on than anyone else. Kessler would always single him out, and whatever Schwartz did, Kessler was not pleased with it and scowled at him,

– Not like that!…

This was David Kessler’s nature: During rehearsals, he would torment the good actors more than the others. And if you asked him why he never did this with the established actors who, in reality, barely had a crumb of talent, he would answer:

– And if I say this to them, will it help us?…I wouldn’t get anything more out of them either way… But I’ll get a lot more from an actor with talent…

During those rehearsals, he made Schwartz so depressed that it was no wonder that Schwartz really took it to heart, and a day before the performance he told us that he wasn’t able to perform because he didn’t feel well. So they gave his role to Simonoff, and Kessler didn’t say anything to him but just let him perform the role however he wanted…

Kessler only delighted when he had the chance to put on a better piece written by a good dramatist - it was like a yontif for him. But not so for the bad pieces; he used to say that having to recite the lines the “Professor”2 wrote was just like chewing oakum. When performing those kind of plays, he would make fun of everyone’s role - and indeed his own role too - and there was such confusion on stage that nobody knew what on earth he was doing…

He clashed with the actors in troupe many times over the fact that, often, he didn’t even know his own role, and many times it blew up into a whole debacle.

I remember how once, in Brooklyn’s Lyric Theater, we put on Goldfaden’s historical operetta Bar Kochba, and they gave me the role of the Roman governor. Kessler, apparently, had no real desire to play Bar Kochba. As usual, he relied on the fact that he had played the role of Bar Kochba many times before, so he didn’t bother to study it or rehearse at all.

This was during the scene where the governor, drunk, sits on the throne and his men come to him to tell him that Bar Kochba wants to see him. I knew my role well because I studied it well, and like a true Roman governor, I said my line great fanfare:

– Bring him here, but first take his sword!

And then Kessler, in the role of Bar Kochba strode forward - tall, strong, healthy, vigorous, looming. And when he looked at me, such a little governor on such a big throne, he apparently thought it was so amusing that he couldn’t help himself - when he turned to speak to me, he didn’t call me governor, but:

– Governium!3

And you could tell that he was barely able to keep from bursting out laughing… In this mischievous mood which suddenly came over him, he forgot the line he was supposed to say. He knew well that even two seconds of silence on the stage is like an eternity, so angrily began to grumble at the prompter to “give him a seed,” all the while looking at me and blurting out the only word he could think of:

– Governium!

At this point the mood became more tense. I felt like the audience was starting to lose patience, and I heard how here and there they were starting to laugh at us. I took this very personally because, by the way Kessler behaved, it seemed that he, Bar Kochba, was making fun of the fact that such a grand Roman governor was just a small little man. I suddenly grew angry and, with a grand gesture from the throne, I issued an order to the servants:

– Take him away, this Bar Kochba, and choke him!

These were, of course, my own words. They were not part of the play. But I delivered the line in such a way that went well with all the chaos that Kessler brought onto the stage. I had no other choice…

After that happened, it was very hard to turn things around to be able to continue the play. When the act ended and I was back in my dressing room, irritated and enraged at what had happened, I heard a loud racket from a dressing room upstairs where Kessler’s room was. And soon I heard steps, and Kessler’s servant came to me and said:

– Mr. Kessler wants you to go up to see him!

But I did not want to:

– I will not go! - I fumed back at him. - If he wants to see me, then he should come down to me…

And so he came down. But he didn’t come to my dressing room; he stopped on the steps and shouted at the top of his lungs:

– Where is he, the Philadelphia “big shot”?

And when he sent for me again, I called back that the “Philadelphia big shot” has a name and that name is Mr. Kasten…

In my anger, I stood my ground. When Kessler, still standing on the stairs, called me “Mr. Kasten,” I came out to see him. I was sure that this time we would have a big fight, and afterwards we would never speak to each other again…

But it went entirely differently. At first, Kessler was angry, and he scolded me for doing such a thing to him on the stage. And when it was my turn, I scolded him back for not knowing his own role, he started to actually listen to what I was saying. With a bowed head, he listened to every word, and then he was silent. Even when I criticized him for at times being cruel and never taking responsibility for it, he was silent. And when I was finished, he took me by the hand and said to me, in an imploring tone:

– Kasey, let’s forget about it!

Just as suddenly as he, the great artist David Kessler, became as angry as a wolf, he became as gentle as a little lamb - and right on the spot, too. When he realized that he was in the wrong, he apologized.

In general, David Kessler was not one of those stars who wrote down every wrong done to him in a little black book. He didn’t keep a record of how the actors in the troupe behaved. He was not a vindictive person. He was able to go easily from angry to calm, from furious to brotherly. This was his nature. And he hated actors who behaved like high and mighty artists when in reality they were pathetic souls with little talent…

Many actors saw him as their enemy and spoke out against him as the worst man in the world. Kessler knew this and laughed about it, and when he spoke of such actors he often said:

– You see4, he doesn’t understand, the idiot, that if he only had any talent and played a role well, people would see him as a man… You know, a real life man. And I would be the first to applaud him…

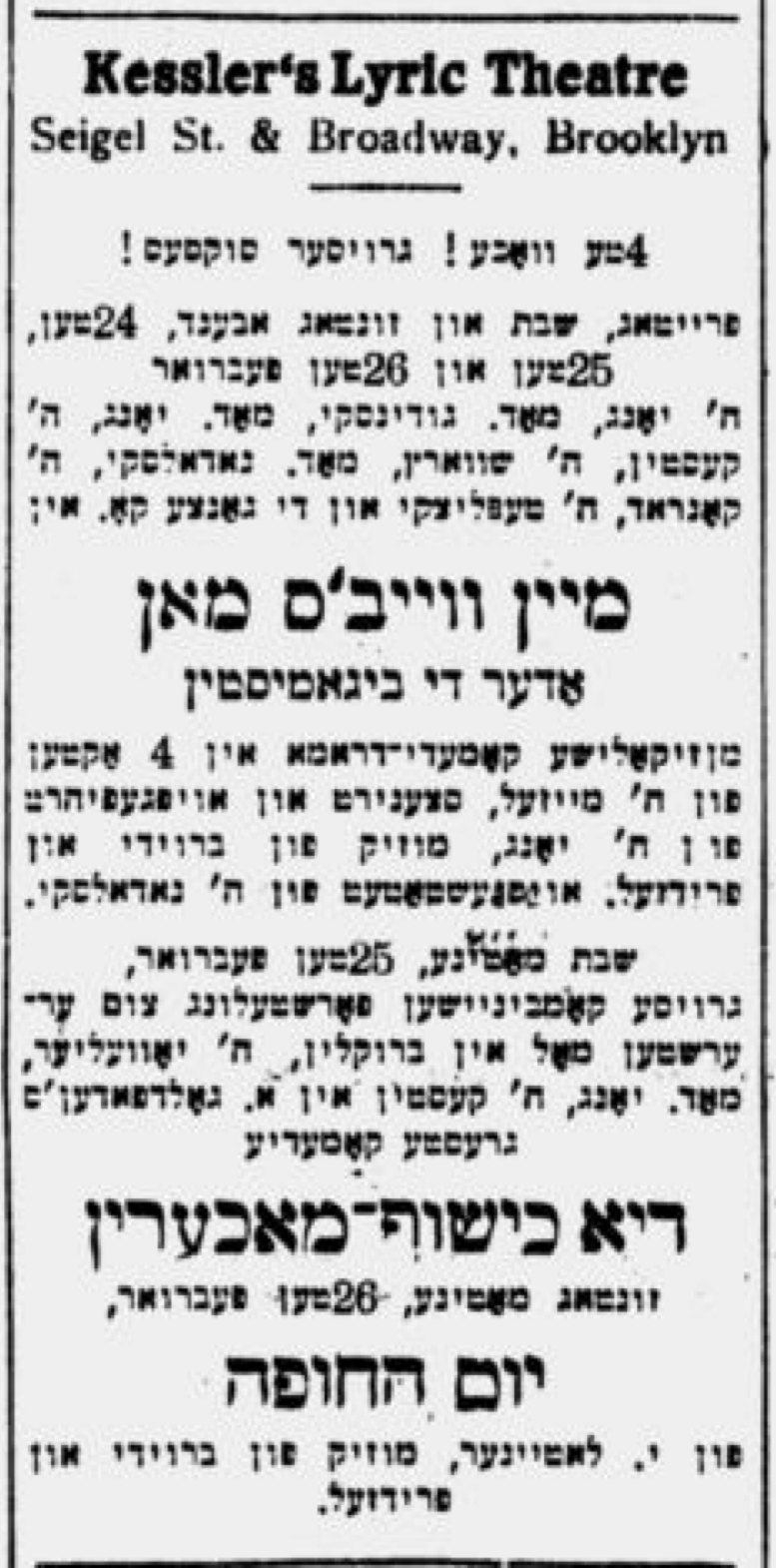

The whole season in the Lyric Theater went on like this; I had a lot of good times with Kessler, and a lot of not-so-good times. And at the end of the season5, there was talk that Kessler was going to choose some actors among the two troupes at the different theaters and travel around the provinces with them. Boaz Young immediately came up with a plan to stage a new comedy in the Lyric Theater called Mayn Vayb’s Man, oder Di Bigamistn. The play was originally written by Hyman Meisel, but Young had also lent a hand6, and he had in mind that the comedy should have a role that his wife, the actress Clara Young, who was not yet famous, could have a chance to shine in.

When the group of actors was being put together to head out to the provinces, Boaz Young told Wilner:

– Kessler can take whoever he wants, but I ask of you one thing - that he not take Kasten and Clara Young with him. I need them both for the comedy Mayn Vayb’s Man.

In this comedy that Young had high hopes for, there was a role for an assimilated German Jew, a fop who behaved very properly. They gave this role to Louis Heyman, but when Kessler came back from Chicago, he insisted that Heyman must be removed from the role and replaced with Schwartz. And when Kessler wants something, you have to give it to him. There’s no talking to him about it, and so indeed the role Louis Heyman had been playing in Hyman Meisel’s Mayn Vayb’s Man was given to Maurice Schwartz. And he was really excellent in it.

This was at the end of winter 19117. Audiences really enjoyed this play. But Kessler wasn’t terribly interested in it - not with the production nor with the play itself. When he first came back from Chicago, he was eager to see what we had been up to without him. But when he came to the theater to see the performance and he was asked what he thought of the play, he answered in his characteristic way…

–Well…it sounds human.8

He also said that the actors did a good job overall, and to those close to him, he said that he now saw that Maurice Schwartz was really a very good actor…

While we were putting on the comedy Mayn Vayb’s Man in the Lyric Theater and Boaz Young was very pleased with his accomplishment, Kessler and part of the troupe were traveling around the cities near New York. From time to time, he came back and soon after left again to play his repertoire. When he heard that we were taking the comedy Mayn Vayb’s Man to Philadelphia for Pesach, he told us that he thought this was a good idea and he would come to Philadelphia to perform with us, and he would step into Young’s role…

He liked this role, and so he played it…

He was of course being honest when he said that he liked the role, because he was an honest man by nature. But, as it turned out, once he started getting into the role he changed his mind and grew disinterested in rehearsals. And when he took a disliking to something, there was no talking him out of it, and we realized that no good would come of this…

And indeed this is what happened - In Philadelphia, Kessler played the role in the way he usually did when a role didn’t appeal to him. He simply couldn’t take it seriously. At every performance he made a mockery of it and no one could perform their role properly alongside him. And it was no use to beg him to stop. It didn’t help for Madame Clara Young to cry, either. Kessler just couldn’t take the play or his own role seriously.

And in the end, the audiences felt we were just making a mockery of the whole thing, and they stopped coming to the theater altogether…

Maurice Schwartz↩︎

recall, Professor Moishe Ish Horowitz Halevy wrote shund plays↩︎

!צעזאַריום↩︎

These two words in English↩︎

more likely, this was halfway through the season in January or so↩︎

he staged and directed the show, and presumably had some say in how it was written↩︎

Again, Sam is correct about his timeline↩︎

Kessler speaks in English here.↩︎